One Facebook group has repeatedly caught the media’s attention. The group was called ‘”Israel” is not a country! … Delist it from Facebook as a country!”‘ Despite the opinions of experts who highlighted the racist nature of the group, Facebook refused to take action. After unsuccessfully lobbying Facebook for intervention, an organization known as the Jewish Internet Defense Force (JIDF) took control of the Facebook group in late July 2008 and began to manually dismantle it from the inside. The rise and fall of this group, and its ultimate shutdown by Facebook, highlights open questions on the right response to online hate in user generated content.

Contents

Meet Facebook

A Facebook hate group

What makes this group different?

The JIDF response

Responding to hate in user?generated content

Meet Facebook

With over 115 million users, Facebook is the largest social networking site on the internet.[1] It was initially limited to colleges in the United States, though later expanded to educational institutions in other countries and then to the general public.[2]

Facebook allows users to share personal information, join groups, send private messages and leave public notes on either a group or an individual’s “wall” (a section of screen real estate designated for this purpose). Members can also share photographs and multimedia and install and use third party applications based on the Facebook platform.

Facebook’s founder & chief executive officer is Mark Zuckerberg, a Jewish self made billionaire aged 24. The valuation is based largely on Microsoft’s investment of $240 million to buy a 1.6 percent stake in Facebook in 2007.[3] Rather than going public or selling out, Zuckerberg has expressed a desire to develop the technology and push the boundaries. He believes in an “intense focus on openness, sharing information, as both an ideal and a practical strategy to get things done.”[4] Without appropriate safeguards including a culture of positive engagement, the things that get done might, in this author’s opinion, be for better or for worse. Asked if Facebook would take proactive measures to fight against antisemitism, Zuckerberg stated that Facebook does not need to be proactive about it and that Facebook users should use the platform to generate more worldly perspectives.[5]

Zuckerberg seems to have missed that most of his Western audience take it for granted that this worldly perspective would include the championing of civil rights and mutual respect. The values of democracy, freedom of speech, and grass roots activism are things Facebook is assumed to stand for, but perhaps only in the West. Facebook could as easily be seen as the ultimate form of dictatorial control. Imagine the impact Facebook could have had for the Soviet Union if respect for communist values meant Facebook handing over the keys to the community party for all members residing in the Soviet Union. Imagine the power Facebook could have had for indoctrination and the search for Jews if it had been available to Nazi Germany and in a show of respect, access to data on those people living under Nazi control were handed over to the Third Reich. Not all values are equal, and Facebook’s founder is in a uniquely powerful position in modern society. Companies the world over are only slowly waking up to corporate responsibility. Facebook’s push for openness is to be commended as a value, but it is a value from the technical world and, while Facebook’s roots lie in the technical world, it is now such a part of modern society that a wider review on impact and opportunity is needed and this inevitably must include an approach against online hate.

Left to their own devices in a Wild West like atmosphere, those using Facebook have been pushing the boundaries, including the boundary of acceptable content. Facebook is a private company, so even in the United States, First Amendment rights do not apply. The rules governing what is permitted are made by Facebook itself, and published in the company’s Terms.[6] The rules include a prohibition on “content that, in the sole judgment of Company, is objectionable or which restricts or inhibits any other person from using or enjoying the Site.” Facebook also has a code of conduct, which states that “certain kinds of speech simply do not belong in a community like Facebook” and enumerated examples including material that is “derogatory, demeaning, malicious, defamatory, abusive, offensive or hateful.”[7] Despite these conditions of use, Facebook has in many cases failed to act or has taken the approach of only acting on topics receiving sufficient external negative publicity – even in the Facebook world the press retains its power.

A Facebook hate group

The group “Israel” is not a country!… … Delist it from Facebook as a country![8] was a Facebook group established around January 2007. A group with an almost identical name and description was created in the Hi5 social networking site on January 9, 2007.[9] That group today has only 1,076 members, while the Facebook group at its height had over 48,000 members, over 120,850 posts, over 150 videos and over 100 photographs. While some of this content was in disagreement with the nature of the group, the majority was decidedly anti-Israel and often antisemitic.

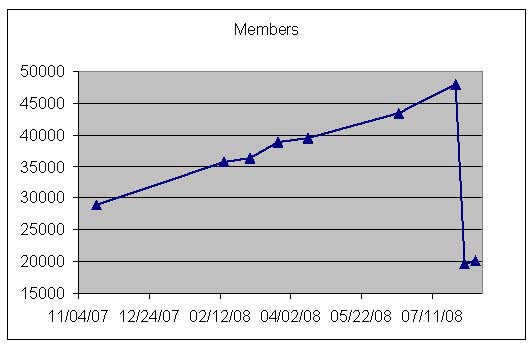

The long running controversy was mostly likely started by Facebook itself when, in October 2006, it removed Palestine from the list of countries people could join. It had been included in the original list but was now replaced by an entity known as “Gaza and the West Bank.” Some Palestinians objected to this, claiming it advocated a position that denied Palestinians ownership of the old city of Jerusalem as well as East Jerusalem. Facebook quietly restored Palestine to the country listing in early 2007.[10] Shortly thereafter a group was established in protest at the re-inclusion, and another group, the now infamous “Israel is not a country” group was created in response.[11] The growth of the group from October 2007 until it was closed by Facebook around September 1st 2008 is shown Figure 1.

| Figure 1: Growth and decline of a Facebook hate group. |

While they may have started off in a similar manner, there was something very different in the nature of the “Israel is not a country” and “Palestine is not a country” groups. The difference is not about international law or the legitimacy of countries. In the electronic world there is no requirement to mirror facts on the ground, comply with international standards, or even include all countries in any given list. To give one example, Israel and about four other countries are missing from the list of countries in the ‘causes’ application (in this case it is not included in the donations section and the missing listing means people in Israel can’t donate money via Israeli credit cards). These things happen, people complain, and usually they get fixed.

The “Israel is not a country” and “Palestine is not a country” groups differed in size, but this too was not the fundamental difference, though it had an effect on the impact the groups could have. The most popular “Palestine is not a country” group has 3,353 members at the time of writing. This is less than 7% of the size of the “Israel is not a country” group – prior to it being taken over and members being booted out by the new administrators. Size matters, but it is not what made this group so different.

What makes this group different?

What makes “Israel is not a country” different from other groups in Facebook is the way it is used. The “Israel is not a country” group was not designed to seriously protest the listing of Israel in Facebook, it was simply part of Facebook politics. That however changed as more radical elements joined the group – something Facebook itself seems to have missed. The nature of a group can change.

The earliest press report on the group appeared in the Toronto Star on May 3, 2007.[12] The author, Antonia Zerbisias, notes a proliferation of groups and counter groups noting that “not unlike college campuses in the real world, when it comes to Israel, it’s an all-out war … of words.” Zerbisias also, it says in the article, contacted Matt Hicks, senior manager of corporate communications at Facebook who had until then been unaware of the problem. This article establishes that Facebook knew of the group for over a year before the takeover, and for over a year Facebook decided to do nothing. If Zerbisias’ analysis of this as a college campus style war of words remained accurate the group would not have grown as large as it did, nor would it have attracted the attention it received.

The change that occurred is that this protest group became decidedly anti-Israel and antisemitic, attracting more like minded Facebook members and changing administrators a number of times. Once Palestine was re-instated, the group’s goal was met, and the collective membership began forming new goals. The group’s logo, a map with Israel entirely replaced by “Palestine” promoted replacement geography in a similar manner to the anti-Israel campaign in Google Earth.[13] The group became highly linked with anti-Israel and antisemitic websites and campaigns. It was used as a base to promote general anti-Israel sentiment and to promote an ideology that advocated the destruction of the Jewish state. The group with its large membership base was used as a recruitment ground where new campaigns against Israel could prosper.

The role of this group was promoting online hate, and specifically online antisemitism. As a result it drew significant attention in early 2008. Addressing the Global Forum to Combat Antisemitism in February, I presented the group and highlighted its use of apartheid rhetoric and clever use of denial. Half the statements in the group’s introduction were antisemitic, the other half were designed to fend off charges of antisemitism. The New York Jewish Week carried a front page story on “Antisemitism 2.0” on February 20th 2008, noting the growth of the “Israel is not a country” group.[14] That report was partly based on a draft of the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs’ “Online Antisemitism 2.0” report[15] which provided the first extensive coverage of antisemitism on the Social Web and coined the phrase ‘Antisemitism 2.0’. The”Israel is not a country” group was one of two detailed case studies examined in the report. Particular attention was paid to the group’s clever introduction of itself as a group against racism, while simultaneously attacking both Israel and the Jewish people. Israel, it claimed, has no right to exist.

The introduction was reused in 75 different groups which anti-Israel elements took over in a very similar manner to that used five months later by the JIDF. The antisemitic takeovers were originally reported in the press in February.[16] Many of the groups taken over had names completely unrelated to the conflict. They included local sports groups, or film appreciation groups. The common thread is simply that the groups had their location set to Israel or otherwise gave themselves away as Israeli or Jewish interests. Some of these groups are still up with the original message still visible. The message is a diatribe familiar to any who deal with antisemitism; Israel is “an apartheid regime,” Israel “has no right to exist,” “Israelis accuse people of anti-Semitism every time someone criticizes Israel,” “Arabs are Semites…unlike most Jews,” “80-90% of Jews today are Ashkenazi (which is the term for European Jews that are descendants of converts),” they “use the holocaust to silence critics of their own crime,” “Israel never met the conditions for its entry into the UN,” the lies go on in some of the remaining clones despite the ongoing efforts of the JIDF.

Not all the attention showed the group in a negative light. Ala’a Ghosha, the hostess of a TV show aimed at teenagers, discussed the “Israel is not a country group” on official Palestinian TV in March 2008. She praised the group, describing Facebook as “a new battleground between the Arabs and Israel” and encouraged viewers to join it.[17]

The JIDF response

On July 27, 2008, the Arutz Sheva Israel television channel published a short report titled “Jewish Activists Hack Anti-Semitic Facebook Group.” The report notes how the Jewish Internet Defense Force (JIDF) had taken control of the “Israel is not a country” group. The JIDF has confirmed for us that the takeover occurred earlier that day.

Following the takeover, the JIDF worked around the clock to empty the group of members. Once a group is empty, it can be deleted. As a first step the problematic description, multimedia and the wall were removed – already significantly mitigating the hate this group was promoting.

The Jerusalem Post followed up with a story on July 29.[18] This corrected the misrepresentation of the JIDF as hackers. It was certainly a takeover, but nothing illegal or indeed outside the rules of Facebook had occurred. Next, in the UK, the Telegraph picked up the story “Facebook: ‘Anti-Semitic’ group hijacked by Jewish force” the story headline declared on July 31.[19]

Hate groups picked up the story too. The Neo-Nazi site Stormfront had the story almost from the startas did the forums at Al-Jazeera. On Facebook itself two groups were immediately set up against the JIDF.

On August first, only a few days after taking over the group, the JIDF lost control of the group. The group’s size had been drastically reduced, the multimedia was gone, as was the wall, but the group’s problematic description was immediately put back. Even if the JIDF had maintained control of the group, setting up a new group takes only a few clicks. The JIDF action did, however, have an impact.

During the few days when the JIDF controlled the group, it expelled 59% of the group’s membership. Based on the membership increase since JIDF lost control, we estimated that it would take the group between 12 and 18 months to recover back to its former levels. This was based on the assumption, later proved incorrect, that neither the JIDF nor Facebook would intervene during that period.

Following the press coverage about the JIDF, a Wikipedia article on the JIDF was created. The article soon attracted the attention of known anti-Israel Wikipedia editors. Even the user who previously deleted all references in Wikipedia to this author’s website countering online hate (www.ZionismOnTheWeb.org)[20] participated. In the resulting discussion the antisemitic nature of the Facebook group was challenged. This challenge was successfully met with references to articles and reports about the group. Shortly after, it became the consensus opinion that there was enough evidence that calling the group antisemitic in Wikipedia was legitimate, Facebook itself then intervened and the group was shut down entirely. The timing may have been coincidental, but this seems unlikely given the length of time Facebook has left the group up and defended it as no more than another opinion.

While Facebook ultimately got it right, this would not have happened without the JIDF’s intervention both in Facebook itself and later in Wikipedia. Nor would it have happened without the attention in the press and the research that led to this attention. Is this really the way society at large should handle instances of online hate?

Responding to hate in user-generated content

Facebook is not the only place where user generated content includes the promotion of hate. Google Earth has come under fire for allowing replacement geography,[21] Ebay came under fire for its role in selling Nazi memorabilia and other goods that promote hate,[22] and Craigslist has had issues with racist accommodation postings.[23] In all these cases the companies responsible have acknowledged the existence of the material and sought ways to resolve the issue. In this case, after a year of inaction by Facebook itself, the users themselves stepped in. Well, some of them at any rate. This seems in keeping with Zuckerberg’s hands off approach on the topic of antisemitism and his desire for users to resolve these matters within the Facebook platform. Facebook’s ultimate intervention was perhaps a result not of enlightenment, but of risk management. Had the group continued to operate once the user community at Wikipedia agreed it was racist, Facebook would be clearly acting against its terms of use in a very public manner.

The actions of the JIDF do, however, raise interesting questions. If they acted within the law, and within the Facebook terms of service… did they do anything wrong? Should similar attempts be encouraged, or avoided? The shutting down of groups is censorship, but is censorship always the wrong approach? The most common approach to antisemitic websites (the main focus prior to the advent of Web 2.0) was to push for the groups to be shut down by their internet service providers. Even in this case many were, all along, urging Facebook to step in and remove the group. There are really only two differences between what almost occurred (had the JIDF been completely successful) and what occurred when Facebook intervened.

The first difference is that Facebook can shut down groups far more easily than users can. As the owner of the platform, Facebook also has the legal and moral authority to determine when a breach of the rules has occurred and to take whatever action it sees as appropriate. The result of direct intervention is usually new protest groups, added publicity and accusations of “political” positions being taken by the platform provider. This occurred in October 2006, and again in March 2008[24] with other controversies. Facebook, however, as a multi-billion dollar company with enormous power (absolute power, in fact, inside the Facebook world) needs to realize it cannot avoid these issues. By simply stepping back and trying to give everyone whatever they ask for, Facebook becomes a platform open to misuse and abuse. Despite its terms and conditions of use, Facebook is ill prepared to deal with Antisemitism 2.0. This new generation of online hate is designed to appear socially acceptable. As such, it aims to have itself classed as legitimate political discourse. Allowing such hate speech to be published is indeed taking a position, whether Facebook will admit it or not.

Facebook itself is falling victim to those pressures that help spread Antisemitism 2.0, the social acceptability of anti-Jewish racism online. Given its responsibility to Facebook users, not to mention to society at large, Facebook’s hands off approach, with intervention as the last resort, is legitimizing online hate and allowing it to spread. One hopes that, at Facebook headquarters, the senior management team will see the need to take another look at the implementation of the company’s terms of service and the need to consider more carefully what counts as legitimate discussion and what counts as the promotion of hate. Relying on Wikipedia is not the solution.

The wider problem can only be solved by Facebook, either voluntarily or, through external pressure and legislation at some distant point in the future, taking a more active role against online hate. The Facebook platform is too powerful a tool to let fall into the hands of those promoting hate. The only question is who will realize this first: Facebook, the public or the legislature.

As for the JIDF, it’s a Wild West out there and until something changes. I’m sure they will be proactively present. Some will agree, some will disagree, and Facebook will continue to hope, in vain, that the problem will sort itself out without Facebook’s own intervention being needed.

About the author

Andre Oboler is a Post-Doctoral Fellow in Political Science at Bar-Ilan University and Legacy Heritage Fellow at NGO Monitor in Jerusalem.

Web: http://www.ZionismOnTheWeb.org

E?mail: oboler [at] zionismontheweb [dot] org

References

Anti-Defamation League (ADL), 2001. “ADL applauds eBay for expanding guidelines to prohibit the sale of items that glorify hate,” press release (4 May), at http://www.adl.org/PresRele/Internet_75/3820_75.htm, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Michael Arrington, 2006. “Facebook just launched open registrations,” TechCrunch (26 September), at http://www.techcrunch.com/2006/09/26/facebook?just?launched?open?registrations/, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Amanda Beck, 2008. “Craigslist cleared over racist and sexist ads,” News.com.au (17 March), at http://www.news.com.au/technology/story/0,25642,23385890-5014239,00.html, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Facebook, 2008a. “Terms of Use” (23 September), at http://www.new.facebook.com/terms.php?ref=pf, last accessed 29 October 2008

Facebook, 2008b. “Group: ‘Israel’ is not a country!… … Delist it from Facebook as a country!” at http://www.facebook.com/, accessed 12 August 2008

Facebook, 2007. “Content Code of Conduct” (24 May), at http://www.new.facebook.com/codeofconduct.php, last accessed 12 August 2008

Hi5, 2008. “Group: ‘Israel is not a country’… … Delist it from hi5 as a country!” at http://hi5.com/, accessed 12 August 2008.

Catherine Holahan, 2008. “Facebook’s new friends abroad,” Business Week (14 May), at http://www.businessweek.com/technology/content/may2008/tc20080513_217183.htm, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Megan Jacobs, 2007. “Facebook sparks ‘Palestine’ debate,” Jerusalem Post (10 October), at http://www.jpost.com/, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Itamar Marcus and Barbara Crook, 2008. “PATV lauds Internet site calling for Israel’s elimination,” Palestinian Media Watch (14 March), at http://www.pmw.org.il/Bulletins_apr2008.html, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Ellen McGirt, 2007. “Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg: Hacker. Dropout. CEO,” Fast Company, issue 115 (May), at http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/115/, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Matthew Moore, 2008. “Facebook: ‘Anti-Semitic’ group hijacked by Jewish force,” Telegraph (31 July), at http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2478773/Facebook?Anti?semitic?group?destroyed?by?Israeli?hackers.html, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Andre Oboler, 2008a. “Google Earth: A new platform for anti-Israel propaganda and replacement geography,” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, volume 8, number 5 (26 June), at http://www.jcpa.org/, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Andre Oboler, 2008b. “Online antisemitism 2.0. ‘Social antisemitism’ on the ‘Social Web’,” Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, number 67 (1 April), at http://www.jcpa.org/, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Nick O-Neill, 2008. “My interview With Mark Zuckerberg,” AllFacebook (11 March), at http://www.allfacebook.com/2008/03/my-interview-with-mark-zuckerberg/, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Reuters, 2008. “Facebook face-off: Settlers win right to list country as Israel, not Palestine,” Haaretz.com (17 March), at http://www.haaretz.co.il/hasen/spages/965215.html, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Stephanie Rubenstein, 2008. “Jewish Internet Defense Force ‘seizes control’ of anti-Israel Facebook group,” Jerusalem Post (29 July), at http://www.jpost.com/, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Tamar Snyder, 2008. “Anti?semitism 2.0 going largely unchallenged,” New York Jewish Week (20 February), p. 1, and at http://www.zionismontheweb.org/antisemitism/antisemitism_2.0_going_largely_unchallenged.htm, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Brad Stone, 2007. “Microsoft to pay $240 million for stake in Facebook,” New York Times (25 October), at http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/25/technology/24cnd-facebook.html, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Antonia Zerbisias, 2007. “Playing politics on Facebook,” Toronto Star (3 May), at http://www.thestar.com/News/article/209925, last accessed 29 October 2008.

Originally published as: Andre Oboler, The rise and fall of a Facebook hate group, First Monday, Volume 13, Number 11 – 3 November 2008

One response to “Andre Oboler, The rise and fall of a Facebook hate group, First Monday 13(11 )”

[…] The Rise and Fall of a Facebook hate Group […]